Information Technology (IT) Pioneers

Retirees and former employees of Unisys, Lockheed Martin, and their heritage companies

Component Engineering, Chapter 42

1. Introduction

To the customer we always appeared as a company with either a program manager or a project engineer as the primary customer interface. Behind every program manager or project engineer there was a multi-talented team of experienced personnel who were specialists in their individual fields. We didn't just buy parts, we specified parts requirements so that the parts would perform as we needed them to in the rugged environments of shipboard, the field, and space.

Component Engineering tested and controlled the parts which were procured to assure quality products. Our design engineers worked with 'de-rating rules' for all components so that any designs would not overstress the limits of any component.

The Purchasing Department worked hand in hand with Component Engineering to process orders and interact with suppliers. [lab]

Product Assurance included the Quality Control (QC) functions as well as a traveling cadre of inspectors who visited component suppliers to urge them to adopt quality standards that met our rigorous standards.

We had detailed manufacturing processes in place with critical point Quality Control inspections years before the International Organization of Standards (ISO) began formalizing the ISO 9000 series of requirements for manufacturing excellence. [lab]

2.0 Component Engineering

Component Tidbit

Larry, the change to the germanium transistors in 1962 was due to the low shock capability for the existing devices. Lee Grandberg along with the Component Engineers came up with a device from Westinghouse that could withstand beating the transistor against a vice when held by the transistor leads. This solved a fragile device problem. Other vendors joined in shortly after. Jack Metzger

2.1 Component Analysis by Larry Bolton

Univac Defense Systems designed military grade computers. Most components

were electrically rated for operation over a case temperature from -55C

to +125C. Back in the 60s and 70s, most integrated circuit electrical

testing at temperature extremes was done by soaking the circuits in

a hot or cold box, removing them, then quickly testing them in a socket

before they warmed up. Usually, the box temperature was set a few degrees

higher or lower than the desired temperature to account for some warming

during the transition. This was good only for cold start characteristics

and the parts quickly self heated so readings were no longer valid.

This was not adequate for electrical characterization which can take

several seconds or minutes.

Univac developed an apparatus in which a thermal air column was continuously

directed at the bottom of the device under test. It included a heater

for the hot temperature and dry liquid N2 for cold temperature. Temperature

was controlled by monitoring the temperature of the exiting air stream

just below the circuit under test. This held the temperature constant

at any desired temperature for indefinite periods. After the initial

prototype was shown to work, the thermal air column was integrated with

our electrical test systems. A hole was drilled thru the bottom of the

test socket so the air jet would impinge directly on the bottom of the

component under test. One of the main problems with this system was

the tendency for frost to form [especially in summer] on the test socket

resulting in intermittent connections. The socket had to be thawed out

and frost air-blasted off the socket contacts. A cover over the test

socket also helped.

This is just another example of apparatus we developed for in-house

use because there were no adequate things available on the open market.

We successful loaned this apparatus to Motorola to correlate our data

with their test methods. ![]()

2.2 Univac Minuteman Program: A Short Story About Pulse Transformers (early 1970s)

One of the components used extensively in the Minuteman memory drawer was a pulse transformer. Each transformer consisted of a small core with primary and secondary windings of very small gauge wire. Four of these transformers were potted in a 16-lead dual-in-line package which was about 0.3 inches wide and 0.9 inches long. The fine wire leads from the transformer were welded or soldered to the inside pads of the package leads. An epoxy plastic compound was injected to form a body for the finished component.

Each electrical component in the Minuteman computer had to undergo rigorous qualification testing which included environmental tests: including temperature cycling, shock, vibration, and life test. Two nationally known companies were represented by the samples which would be qualification tested. At that time, southwestern Minnesota was considered an economically depressed area. A University of Minnesota graduate named Oscar A. Schott had established a business based on the design and manufacture of transformers. He had a small shop in Marshall, Minnesota which specialized in pulse transformers and other small transformers. I agreed to include samples from the Schott Company in the qualification test, assuming there was little chance they would pass. After all tests had been completed and corrective action had been attempted on the failures that had occurred, the Schott pulse transformers were the only ones that had passed. The main problems had been the internal lead connection. This created a dilemma for the Univac Minuteman program.

Another requirement of the Minuteman program was that all processes and procedures used in the manufacture of critical components had to be listed and revision controlled. Any changes to the ‘baseline’ were subject to review by Univac for impact to the program. Schott in Marshall was a small operation. All they had were informal sketches and verbal instructions for the assemblers. They also lacked enough people to create the numbers of documents required and needed guidance. Univac in St. Paul formed a team consisting of manufacturing and quality persons to go to Marshall for a week or two and help. They worked with the Schott engineers and manufacturing persons to create a set of documents which would meet Minuteman requirements. The Schott pulse transformers were used successfully for the duration of the program. Eventually, we did qualify two other sources for these transformers.

The former Minnesota-based Schott Corporation, although not an offshoot

of ERA or Univac, has supported several programs at Univac/Unisys defense

systems thru today, both with transformers and power supplies. The Schott

Corporation has been a contributor to the U of M alumni association

and TPT television, among other charities. Oscar Schott was added to

the University of Minnesota Wall of Honor in 1996. Schott Magnetics

is now a world wide company based in San Diego but still has facilities

in Minnesota. They are another company which can attribute part of their

success to the business relationship they had and still have with Univac/Unisys/Lockheed

Martin. [Written and submitted by Larry Bolton]

![]()

2.3

The

Motley Crew

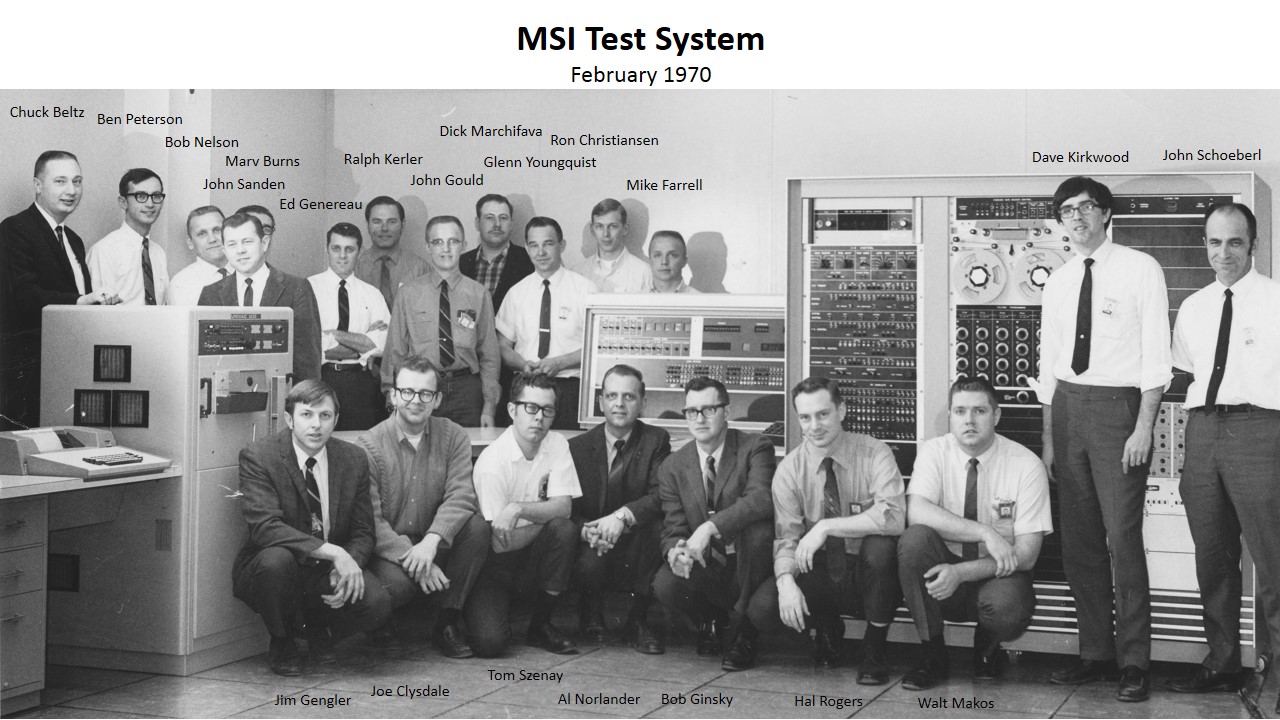

The 'Motley Crew' component engineering group. This 1970 photo commemorates the creation of the automated component tester. The tester in the picture was the DC & Functional tester that Dave Kirkwood designed. Of course, you probably know that the piece of equipment off to the left (in front of Chuck Beltz) is a 1232 I/O Console that was tied to the 1218 computer next to it. This tester was in the mezzanine in plant 5. It was designed and built through the efforts of those in the photo.

We had some bright people designing and building items like this which were strictly for internal use. Many of these people were later at the Plant 8 semiconductor facility. Annotated photo submitted by Ralph Kerler.

Chuck Beltz – Principal Engineer, cost; Ben Peterson –

Development Engineer, thermal environment system; Bob Nelson –

Senior Engineer, scheduling; John Sanden – Engineering Specialist,

thermal system; Marv Burns – Technician B, cable wiring; Ed Genereau

– Engineering Aide, test head; Ralph Kerler – Manager; John Gould –

Development Engineer, programming; Dick Marchifava – Technician A,

card assembly, test fixtures ;Glenn Youngquist – Engineering

Specialist, check out; Rob Christiansen – Technician A, card

assembly; Mike Farrell, Technician A, card layout, programming; Jim

Gengler, Technician A, card assembly; Joe Clysdale – Technician A,

partitioning, wire tabs; Tom Szenay – Technician A, car wire-wrap;

Al Norlander – Technician A, card wire-wrap; Bob Ginsky – Technician

A, thermal system; Hal Rogers – Technician A, chassis wire-wrap,

cable organization; Walt Makos; Dave Kirkwood – Development

Engineer; and John Schoeberl – Engineering Specialist, ACMET II![]()

3. Procurement, Component Acquisition by Mike Svendsen

In the early 60's, two new industries;

computers and semiconductors - and a growing company created a major

challenge for Univac Procurement. How do you specify and receive a high

quality, state of the art semiconductor device when needed, in volume

and at a reasonable price. They also had to manage the limited supply

when it did not meet the demand. Each project within Univac wanted control

of this activity and its documentation. Enough qualified resources did

not exist to do these functions everywhere, and in fact we had to learn

about the new semiconductor suppliers and their devices. Every project

needed something slightly different. The quality levels we were familiar

with were not adequate. Every supplier was promising anything to get

designed in. Procurement could not acquire the necessary volume in time

and at the cost needed by the projects.

Out of necessity in 1962 a close cooperative effort between

all functions was implemented. A mature industry (carbon composition

resistors) was used to work through the issues of project control, documentation,

device upgrades, ordering, and stocking. We combined 33 drawings into

8 Standards which were then used in both Military and Commercial systems.

At the same time, a similar effort was started with semiconductors.

We gathered together all of the device types used in existing computers

and projects and categorized them by function in order to select candidates

for standardization. The specifications were developed and the suppliers

were put through rigorous testing to become qualified. The 20 highest

volume devices were coordinated for all of Univac (both Military and

Commercial.) It was felt that reliability and quality requirements were

the same for both computers. This coordination included specifications,

source selection, negotiation and quality verification. The Univac relationship

with the Semiconductor industry was being developed. There were regular

meetings with the suppliers to discuss new devices and to exchange info

about the quality, price and delivery of devices under contract.

The Reliability of early devices was not adequate - our

Reliability Engineers shouted that message in many papers and forus

in 1963 and 1964. New manufacturing techniques were required and developed

as the devices became smaller and more complex. Feedback on these processing

and assembly changes was crucial to fast corrective actions. The Univac

failure analysis lab analyzed all of the failures and developed new

techniques for identifying and documenting the failure modes to the

suppliers. They took thousands of pictures and we made many visits to

convey the need for improved control of their factories. We audited

their corrective actions and continued to give feedback. We implemented

vender surveillance with resident inspectors to shorten the time to

improved devices.

A Quality Verification Test (QVT) was implemented which required the

destructive analysis of a part from each lot/shipment of a device. These

pictures and analysis checked the die configuration and assembly methods

and provided early warning of workmanship problems or process changes.

All of this information was given back to the suppliers for corrective

action.

Qualified resources - human and machine - were always in

short supply, especially as Univac grew and more plants and organizations

needed semiconductors. It was decided that Univac needed only one major

interface with the Semiconductor industry. The concept of the Semiconductor

Control Facility (SCF) was developed in 1972 based on the experiences

of the ‘60’s. An organization was created in Roseville,

MN., to handle all aspects of the acquisition of semiconductors for

Univac world-wide. This included the gathering of requirements from

all plants, negotiating and placing orders with suppliers, receiving

and verifying their quality, 100% testing, inventorying, and then satisfying

the demands from all plants. We also reported back to the Semiconductor

industry on their performance and rated them against their peers. The

total Univac volume made us one of their largest customers at a time

when attention to every problem was essential. Our quality and overall

performance feedback was the best they received and was very much appreciated

and they used it to improve their support of Univac. SCF remained in

operation in the Twin Cities until 1985 when it moved to California

under Burroughs. During its 14-year existence SCF handled just over

1 billion dollars of the most precious commodity required to build computers.

The cooperative efforts within Univac and with the industry helped

make our Military and Commercial computers the most reliable in the

industry. It was also very helpful to the semiconductor industry during

its formative years.

B.N. Mike Svendsen Univac-1959 to 1984

![]()

4. Product Assurance by Dick Roessler, UNIVAC - 1956 TO 1989

During the post World War II and Korean campaign era, military commanders determined that the existing command &

control, navigation, fire control, weapons, and logistic/supply systems could not be depended on to provide a quick response and effective defense

system for national defense and security. The alleged Cold War was in process and International issues continued to pop up. The analysis performed

by the respective military branches revealed that their systems were often technically obsolete and inadequate in many respects. The commanders

felt that a priority should be given to improve these systems. The systems often had an extremely low Mean-Time-Between-Failures. In particular,

the electronics of many systems they felt needed to be upgraded to the next generation. The need was for a significant improvement of their

readiness of deployed systems.

In the early 1950’s, the U. S. Navy expressed a great interest in the development of digital computer managed systems as an

improvement over analog computers. The Navy became very active in encouraging the development of one of Defense Systems Divisions fledging organization,

Engineering Research Associates to begin work in that area. This combination of Naval leaders and local talent this new company was formed. It soon

became very proactive in the development of digitized circuitry. ERA was acquired by Remington Rand and we know the history as it becoming

Remington Rand UNIVAC. (Referred to as the company in this report.)

Procuring agencies in the Navy, became very cognizant that improving readiness of military systems in an operation deployment must

be given a high priority. It began specifying this important factor in competitive procurements. The company quickly found that in the design

of digital computers, using vacuum tubes in operational equipment would create low MTBF and be a significant readiness issue. We also know historically

that the invention of solid state transistors as discrete components was a significant breakthrough and followed by enhancements with the

advent integrated solid state devices. This achievement was able to breathe life back into future successful digital electronic designs.

The company also began to understand that successful defense contractors would need to develop the capabilities to perform and demonstrate to

defense customers that it possessed the technical disciplines and skills to assure a system/product which would meet any/all contract requirements

of Quality & Reliability. These factors are the heart and soul of Readiness.

The company Contracts Administrators and Program Management recognized that in order to satisfy competitive design contracts and

to qualify for production contracts, would require a very skilled and disciplined technical team. This meant that beginning to develop a technical

concept modifying the transition of a new design product to production.

Design Engineers would take into consideration every detail of the customer contract relative to design specifications including mil-standards and

in particular those relative to reliability and performance criteria. It would also mean that as a team with Production Engineers, that the

design plan would include the building of a prototype and perform testing to assure that not only does it reflect conformance to contract requirements

but that it is reproducible!!! No more throwing a new, untested product over the wall to Production engineers in the factory.

Company management became actively involved in establishing the necessary organizational disciplines and accountabilities to achieve

a high level of customer satisfaction. Product Readiness became the customer and company goal mantra. The company internally interpreted

that for practical purposes, the company would be cognizant of Product Readiness and assure conformance by implementing Product Assurance practices.

This meant that every technical or administrative team member be aware of what is required in achieving the highest level of Product Assurance

and in meeting Design or Production Contract requirements. The following represent some of the disciplines and considerations given to Product

Assurance:

- Product Assurance includes hardware, software, systems, documentation and services.

- Includes disciplines encompassing reliability, & quality.

- Assurance that discrete components meet all of the mil-standard and performance criteria.

- Inspect and perform tests of products being manufactured to assure that the products meet performance requirements; includes environmental tests to assure readiness under adverse conditions in deployment.

- Establish a process of internal auditing of hardware build to assure customer quality audits are satisfactory when held. Have capabilities to perform thorough failure analysis of any discrepancy in contract performance.

- To develop disciplines to assure that vendors and subcontractors are conforming to the purchase agreement or subcontract agreement.

Implied in the above is that in order to

achieve a high level of customer satisfaction and to assure a profitable

contract, compliance with Readiness conditions was paramount. Product

Readiness and Product Assurance was a discipline which evolved over

a period of time and a variety of contracts. The customer during the

1960’s and 1970’s often would provide contractual funding

to achieve the expected readiness. Often times it meant that the company

would work as an Associate Contractor with the Customer’s team

of contractors and funding would be provided to perform additional tasks

during design and into deployment.

As the customer began to become more confident in its system

procurement practices, it began funding contracts to assure that a defense

system during deployment was properly supported. Frequently this was

provided under a contractual agreement to have the company provide Integrated

Logistic Support. This funding was provided to have contractor’s

staff deployment of operating systems by considering the availability

of adequate technical manuals, crew training, repair parts, on-call

technical services, diagnostic programs, etc. This demonstrated that

effective readiness needed to be a commitment on contractor and customer

personnel as well.

Another but somewhat related element of customer Product Readiness was

agreements to perform on contracts requiring the company to prepare

Installation Design Documentation and install deployed products. In

other instances, because of limited military personnel to maintain operational

systems in remote areas, company field engineers would staff these sites.

Often the profit margins on these contracts were quite good because

the contract was tied to performance indicators.

Product Readiness and Product Assurance took a rather significant

detour when special “ruggedized” hardware was no longer

a procurement requirement. Available “off-the-shelf” became

a very common practice. It completely changed the procurement practices

and certainly made for very competitive bidding.

One last thought. The company performed a very important

role by providing exemplary support and service to our military and

civilian agency customers during the early days of introducing improved

customer Product Readiness. Certainly the learning curve for the design,

manufacturing, quality, test and field engineers was rather steep. We

also learned that software, as a deliverable product, needs to develop

similar disciplines and assurance testing that hardware does. A good

lesson for us…..

My hat is off to the many individuals who had major roles

in providing their energy and talent to assure Product Assurance. It

was a great team that evolved and it is a legacy we can be proud of

during the time that Readiness was vital. It probably permitted some

military commanders to feel a bit more secure during the ‘cold

war’.

5.0 Semiconductor Facility Development

Mike Svendsen has written a document about the Semiconductor Facility, embedded in the history of Semiconductors activities by UNIVAC.

6.0 Recollections of Jack Metzger, et al'

1218 and 1219 Designing:

Lowell, the 642A design was completed about the time I hired into Remington Rand Univac. The 642B design was

done in 1962 with Finley McLeod as the project engineer. I was on loan to Finley and was part of the circuit design team. A new total

design effort was required for 1218 and 1219. Don Mager was the equivalent of the project engineer, I don't think that title was

used at the time. We had to develop a whole new set of silicon transistors for push pull and other small signal applications.

Vendors rated the devices at saturation and cut-off and we had to convince them to test them at small signal parameters to obtain the

high speed switching needs for the 1218 and follow on applications.

Larry and Lowell, we used the 15 pin cards until Les Nessler made a much smaller card for the CP-667 program.

This design never caught on and was only used in that design. Don Mager decided that we would use the 56 pin larger cards for the C-3

design after much negotiating with Curt Christianson who was chartered to define the new generation card size. Don got tired of

waiting for Curt and defined the 56 pin card size, we didn't look back. It became the new standard.

Larry, the main reason for converting to silicon from germanium was the operating temperature range for

silicon was greater. As we got new design transistors the switching speeds improved. That is when we went from standard oscilloscopes to

sampling oscilloscopes. [jm]

From Don Mager: Best I can recall - recall is getting marginal - the

most significant logic element change from the 642A to the 642B was

going from NOR logic gates to NAND logic gates, which significantly

reduces the number of transisters required. These reliable,

cost effective, basic logic gates were designed by Lee Grandberg.

As for germanium vs silicon transisters, I don't think we ever

changed to silicon for discrete logic transisters. The change to

silicon logic gates came in the CP667 with integrated circuits and

then the ubiquitous 1001 and 1002 Diode Transister Logic Integrated Ccircuitss. As for the germanium

transistor reliability problem mentioned by Jack Metzger, as I

recall, there was a transistor fabrication process problem with

loose "getters" inside the case sometimes shorting-out the

transistor. It was possible to shake a pc board with a loose getter

and actually hear it rattle around inside the case. These were very

difficult problems to locate since they would come and go. A change

in the transistor fabrication process took care of the problem. It

should be noted that although the logic gates remained germanium,

silicon transistors eventually were used for certain special

functions such as in memory, I/O and power supplies.

The AN/USQ-17 used an entirely different, very complex

"active" logic element designed by Seymour Cray - very difficult to

maintain. The switch to the simple NOR gates in the 642A was an

excellent step forward.

For the record, the 642A logic design team was lead by Finely

McLeod memory; Hy Osofsky control section, Glen Kregness arithmetic

section and Bob Burkeholder I/O section. Bob seems to have been

glossed-over getting due credit, probably because of his untimely

passing resulting from a nuclear radiation exposure incident while

at MIT. I'm proud to say I had the privilege to assist Bob in the

642A design.

Jack, I believe that in addition to the higher temp tolerance, silicon also provided higher current capabilities - thus fewer transistors.

[dvm]

Don, I believe you were right on higher current and better performance capability for silicon technology.

The Navy wanted to wider temperature range at that time. After fifty years its difficult to remember all the details. [jm]

I found my time line in reference to introducing silicon transistor technology into our Univac product lines.

I was reporting to Lee Granberg in 1963 and 1964 when we were required by Navy contract to not use geranium devices for the CP-667 computer

![]() development.

We may have used some silicon on the 15-pin cards but it wasn't a contract requirement. The cp-667 used hybrid logic circuitry that was built

using aluminum wires prone to purple plague and open contacts. Only three computers were built due to the defective hybrids.

The Navy funded an integrated circuit contract to develop the 1000 and 1001 logic devices that were then used on

AN/UYK-7 and C-3. I developed the Navy devices with five different vendors. This effort was supplemented with company money under Ralph Kerler's watch.

development.

We may have used some silicon on the 15-pin cards but it wasn't a contract requirement. The cp-667 used hybrid logic circuitry that was built

using aluminum wires prone to purple plague and open contacts. Only three computers were built due to the defective hybrids.

The Navy funded an integrated circuit contract to develop the 1000 and 1001 logic devices that were then used on

AN/UYK-7 and C-3. I developed the Navy devices with five different vendors. This effort was supplemented with company money under Ralph Kerler's watch.

CP-667 Designing:

We do have some CP-667 cards in the DCHS archives. The attached photo shows three of them.

These are 27 pin cards and are smaller than the 15 pin cards.

One card has six of the hybrids designed by Lee Granberg as mentioned previously.

It is a 4224080 AND-OR Flip-Flop, 2(330/3). There are two each of three hybrid types. The Motorola SC92 (7900034) is a 1-1-1-2 Diode

Gate using nine 1N914 diodes. The Motorola SC94 (7900036) is a dual transistor gate using two 2N2501 transistors (NPN Silicon) with

associated components. I do not have specific data on the Motorola SC90 device but, if numbering is in sequential order and by

extension of part numbers, I believe it is a 7900032 3-4 Diode AND Gate.

There were at least eight hybrid types in this series. I do have data on them that

I got off microfilm back when I had access to the vault. I hope this info reinforces some memories about this stuff. [LBolton]

Larry, I have a few 27-pin pc cards used in the CP-667 probably used for test purposes. You are welcome to anything I may have in my inventory if they are of any value to you. I have been retired for about 25 years and haven't found any use for them yet. [jm]

Jack: When you are ready to part with them, feel free to donate them to the DCHS. I'm sure Lowell or others can help with this. Just about all my artifacts have been turned over. All I have are photos taken before the legacy artifacts were turned over to DCHS. Larry

In this Chapter

- Introduction (left)

- Component Engineering

- Procurement, Component Acquisition by Svendsen

- Product Assurance by Dick Roessler

- Semiconductor Development by Mike Svendsen

- Recollections by Jack Metzger

Chapter 42 edited 7/13/2025.